Merry Gourmet Miniatures © 1988 - 2025 Designed By Bluechip Computer Support

The Use of Spices in Tudor Food

When the Normans conquered Britain they brought with them in their cooking with much more use of spices than had previously been used in Anglo Saxon dishes. Pepper and mustard were the two main spices used. Mustard was home grown, brought over by the Romans, but pepper came from overseas and was a very valuable commodity, often only given as gifts between monarchs and high churchmen, because the spice-trade ships rarely made it as far west as Britain and even if it came overland through Europe it usually did not make it as far as our shores. By the beginning of the 11th Century, English merchants who travelled to the great continental fairs were able to exchange their woollen and linen cloths and tin for these prized spices. Most still destined for wealthy kitchens, but with more secure trade routes, pepper had become cheap enough to be purchased for the small English Manor.

Norman cookery had introduced more spices, pepper alone was no longer enough, now the well-to-do had cinnamon, ginger, saffron, cardamom, nutmeg and cloves, grains of paradise, zedoary, galingale and cubits to flavour their sauces, and season their dishes.

Because all food was organic and eaten in season, the myth that spices were added to disguise bad meat or vegetables is not feasible, it is much more likely that spices were added for extra flavour, as the main food was very bland it needed all the help it could get to add savour.

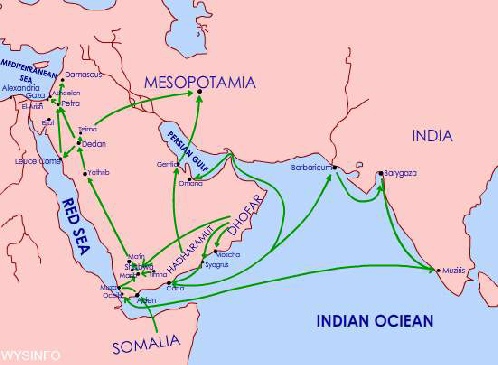

Most of the spices came from the Far East, Southern China, the Molucca’s, Malaya and India, they were carried by overland trade routes to the ports of the Eastern Mediterranean then shipped on Venetian or Genoese ships to Italy. From there they were distributed through North West Europe to be sold at the great fairs of Champagne and Southern Flanders. By the 14th Century Venetian galleys were also sailing to London and Southampton with these luxury wares.

London was the center of the spice trade in Britain for this was the main port where the rich cargoes disembarked. Outside London spices could be obtained periodically at the great regional fairs and the commoner ones like pepper and ginger were sold by itinerant chapman. London was still the centre for the more rare and exotic varieties and what’s more, were available throughout the year, so when members of the household travelled to London on family business, they were often commissioned to bring back several different spices. Of these, Saffron was the most expensive and still being imported from Spain, although by the 15th Century, attempts were being made to grow it in the northern counties and it eventually became an important industry in Cambridgeshire and Essex, especially around Saffron Walden.

In spite of home growing, the spice still remained expensive for it was labour intensive in gathering the stigmas from a lot of blooms, rather than from the cost of carriage from overseas which dictated the final price. Recipes now not only called for individual spices but mixed spices of which the 3 most common were ‘blanche powder’, ‘powder forte’ and ‘powder duce’. ‘ Blanche powder’ was pale coloured from ingredients such as refined sugar, white ginger and cinnamon, beaten to a powder to use on roasted apples, quinces or wardens (pears) or to sauce a hen. In ‘Powder fort’ the hot spices such as pepper and ginger dominated, while ‘powder duce’ was made from some of the milder ones.

Because of cost, in wealthier kitchens spices were carefully looked after, those being used continuously were in charge of the head cook who stored them in a little chamber off the kitchen. The main supplies were kept locked in chests in the wardrobe, a small room which served as a store place for various articles of value and only dispensed to the cook, as he needed them. Some recipes that have come down to us seem to be very heavily spiced indeed for the quantities used, but the quality could have been very variable. The spice routes, first overland then a long sea voyage, then transportation by pack horse again, could mean a journey lasting two to three years.

This was bound to affect the flavour, so although the food could be well seasoned, the result may have been tasty rather than fiery. But whatever the quality they were in constant use and there is hardly an area of cookery that does not use spice of some variety, but it was a long time before imported spices came into the range of the average cottager.